Dearest sinologues, sinophiles, and sinophobes,

At this point, it’s almost a cliché to apologize for the erratic schedule of these dispatches. However, if there’s anything consistent about this newsletter, it’s precisely its unpredictability! We’ve now hit a record number of readers, completed our 20th chapter from another obscure corner of the globe, and we’re marking the two-year anniversary of these earnest, albeit middling, emails. I am immensely grateful for your readership, your sometimes demanding expectations for the next instalment, and your patience with my pretensions.

Nearly 14 years have elapsed since my last visit to this mammoth of a nation, and I returned with as much ambiguity as when I’d departed. Last time, fresh off the buzz of a successful Beijing Olympics and on the ice of a rising China, I was an eight-year-old more concerned with acquiring copycat Lego sets than with geopolitical shifts. Though none of my milk teeth were lost this time around, the ground underfoot was equally transformative, set against the backdrop of what some deem the next cold war and nearly five years since accusations flew of cultural genocide. With many analysts predicting the great Chinese slowdown, the resonance of this visit bore a matured, albeit cautious, curiosity.

The sheer scale of the nation defies simple narratives—this is arguably true for most large states. Yet, here I am, without the luxury to pen a comprehensive manuscript detailing these weeks of travel. Instead, what unfolds in this dispatch is part observations, part analysis, and part open questions from a three-week expedition spanning major urban centres, the lush south, and the remote regions of Xinjiang. For those of you peering through your screens for a Bill Bryson-esque travel memoir or a Project Syndicate-style policy critique titled ‘Taming China’s Dragon,’ let me temper your expectations right away: this is neither. This ink-uilab is split into seven chapters: I. Introduction, II. on the Economy, III. on the State, IV. on global power dynamics, V. on state control, VI. on integration and cultural homogenization, and VII. A Conclusion.

I. Stability above all

Navigating through China’s sprawling expanse, from neon-lit skylines to ancient, ashen Buddhist caves, it’s challenging to clump observations into a singular theme. Nor is it fair to make broad claims about ‘China’ or ‘the Chinese.’ I’d like to caveat any broad generalizations and assumptions as mere observations by a single non-local traveller who does not speak Mandarin. Humbly, it will be aeons before I possess a sense of cultural understanding and historical and linguistic knowledge to comment on China (or any nation, for that matter) with some level of conviction.

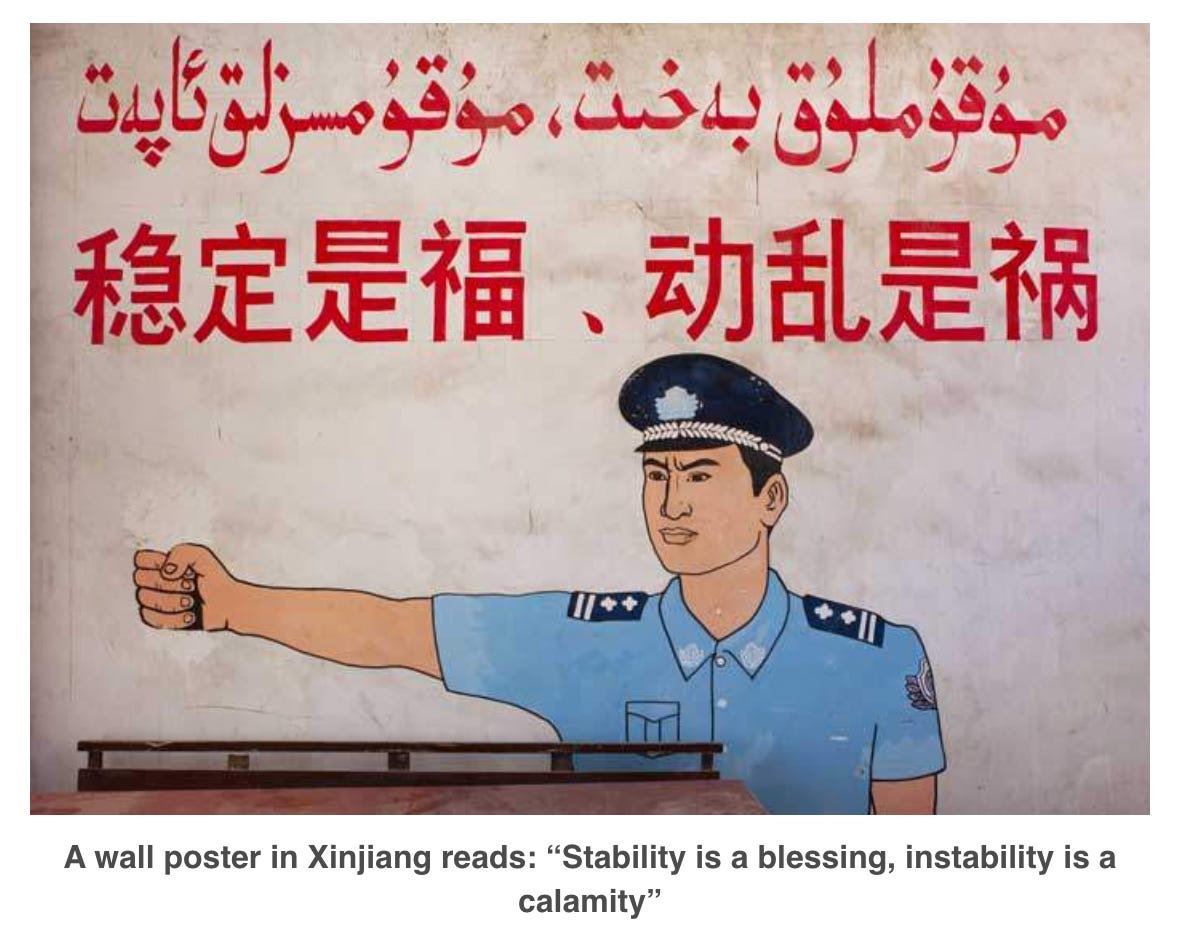

However, if compelled to pinpoint a singular narrative thread for the sake of this essay, it would undoubtedly focus on the motif of a state in relentless pursuit of stability. This pursuit, once seemingly achieved, remains perpetually shrouded in a cloak of paranoia—a condition not exclusively Chinese but observable across many post-colonial states wrestling with their rapid developmental trajectories and historical complexities. I’ve often argued that the Indian state, given its breadth and scale, is similarly paranoid. It’s jittery because it is acutely aware of its own imbalances and fragility, perched on the fulcrum of a very narrow balance, one that could be destabilized by seemingly minor incidents escalating into significant upheavals. The Chinese scenario mirrors this, with the state employing extensive surveillance, economic regulations, internet restrictions, and stringent educational directives to maintain control. The global indices on digital surveillance place China at the forefront, utilizing advanced technology to monitor its citizens far beyond what many democracies would consider acceptable. This web of surveillance extends to social control systems and facial recognition technologies (we scanned our faces an average of five times a day) that regulate public behaviours, underpinning a broader strategy to cement societal compliance. Averse as I am to superficial commentary on this paranoia, it appears less a trait unique to Xi Jinping’s administration than a characteristic inherent to any nation at this stage of development—India under Modi exhibits strikingly similar behaviour. However, when this inherent paranoia is coupled with China’s exceptional state capacity, the dynamics at play intensify, creating a unique set of challenges and responses. More on this later -

II. A Miracle with Chinese Characteristics?

Given my inclination toward economic analysis, the unfolding narrative of China’s economy was particularly compelling during my visit. It's hard not to marvel at what can only be described as an economic miracle. Observing the robust pillars of China's poverty eradication and infrastructural campaigns, one cannot help but recall the arguments presented by Professor Arvind Subramanian in his work, Eclipse. Nearly a decade and a half ago, Subramanian prognosticated with remarkable prescience that “China's Dominance Is a Sure Thing,” an assertion that holds considerable weight even as the nation grapples with a trade war with America, a deceleration in economic growth, bouts of currency volatility, and stringent controls on capital outflows amid a global pandemic. Naturally, the economic miracle of China naturally compels a comparison with India. A lingering question one is faced with is: “Will India be the next China.” I’d strongly recommend this analysis in Foreign Policy by Subramanian and Felman from April for an extensive macroeconomic answer.

One of the most interesting realisations of this trip was the ubiquitous use of facial scanning. One could hop onto a trans-national bullet train or for that matter a flight, without once showing documentation of any sort. Rather, one could just book a seat on an app, show up at the station right before your train, and scan your face at the turnstiles. While China has markedly advanced its digital infrastructure, India’s foray into similar territories, particularly with the implementation of Digi Yatra, has been met with a mixed bag of innovation and contention. Digi Yatra, launched with the aim to streamline airport processes through facial recognition and biometric data, echoes China’s penchant for surveillance under the guise of convenience. However, my personal experiences, coupled with reports of passengers being coerced into this 'voluntary' service, highlight a critical crossroad: the balance between technological advancement and the preservation of individual privacy. The foundational privacy principles, or the lack thereof, raise a spectre of concern that India may tread a path not unlike China's, where the state’s gaze becomes omnipresent. The Internet Freedom Foundation has been doing the brave job of taking the government head-on with its campaign to “urge them to completely withdraw Digi Yatra from Indian airports owing to its large gamut of concerns relating to privacy, surveillance, exclusion errors and lack of institutional accountability and transparency, coupled with the highly disturbing manner in which it is currently being deployed at airports – with reports of coercion and deception, at the cost of passengers’ dignity, privacy, and autonomy.”

Turning our gaze towards the digital economy, China's march towards becoming a cashless society is underscored by the ubiquity of Alipay and WeChat Pay. Reports indicate that cash transactions have dwindled to a mere 3.7% of the total monetary circulation, a testament to the pervasive influence of major payment apps like Alipay and WeChat Pay. These platforms, having revolutionized retail purchases, money transfers, and even transport bookings, epitomize the seamless integration of technology into daily commerce. Yet, this transformation is not without its criticisms. The market dominance of these two giants almost borders on a duopoly, restricting consumer choice and flexibility in the digital payments ecosystem. It is difficult to stress how ubiquitous these apps are - making it nearly impossible to buy a coffee or order at a food stall without scanning a QR code, ordering on a ‘mini-app’ and paying via the app platform. A question we often asked ourselves was, while this was quite difficult as a hurdle for tourists without access to Chinese bank accounts (and hence a WeChat), how difficult would these be for China’s elderly without the technical prowess needed? In stark contrast stands India's approach to the Unified Payments Interface (UPI). Launched as part of the ambitious India Stack initiative, UPI supports a vibrant ecosystem of around 90 different payment apps (as of 2019) spanning from tech behemoths like Google to local startups, reflecting a fragmented market structure that fosters robust competition. This approach not only democratizes digital payments across diverse socio-economic segments but also catalyzes a plethora of innovative solutions tailored to the unique challenges of India's digital economy. The favourable demographics, a large informal sector, and deep-seated inefficiencies, coupled with India's distinct regulatory frameworks, craft a digital landscape rife with opportunities for transformative impacts on economic inclusivity. But then again, as the FT finds, “despite claiming to undermine monopolies, a few big names have managed to assert commanding positions in the digital sphere: PhonePe and Google Pay account for over 80 per cent share of UPI transactions between them.” However, the India Stack still raises many open questions about state surveillance, the digital divide, the centralization of data, and concerns of data privacy and leaks.

Moreover, as we navigate through the bustling streets of Beijing, the sight of bicycles weaving through traffic presents yet another facet of China's urban policy innovation. The presence of multiple competing bike-sharing companies (three big ones, to be precise), underpinned by stringent regulatory limits on pollution and a well-developed infrastructure of bike lanes, offers a pragmatic and eco-friendly solution to urban congestion and environmental concerns. This approach contrasts sharply with the situation in Indian megacities like Mumbai, where the concept of dedicated bike lanes remains largely a theoretical discussion rather than a visible reality.

III. All Under the Sun

Before proceeding, it might be prudent to elaborate on the nature of paranoia that pervades the state apparatus, not merely as a modern-day surveillance phenomenon but as a historical continuum stretching back millennia. Professor Victoria Tin-bor Hui at the Univerisity of Notre Dame eloquently traces this in her exploration of Chinese history, where she suggests that China’s perceived unity is less about natural cohesion and more a product of historical force. She notes, “What is unique about China is not its unity but its precocious capacities for direct rule and military-fiscal extraction which began under the first two unified dynasties: the Qin and the Han. China’s seeming unity is the product of the mutually reinforcing processes of coercive political unification and cultural homogenization.” Here, military conquests didn't just expand territories but systematically flattened cultural landscapes to enforce a homogeneous cultural identity that, in turn, justified the rulers' celestial mandate to govern ‘all under heaven’.

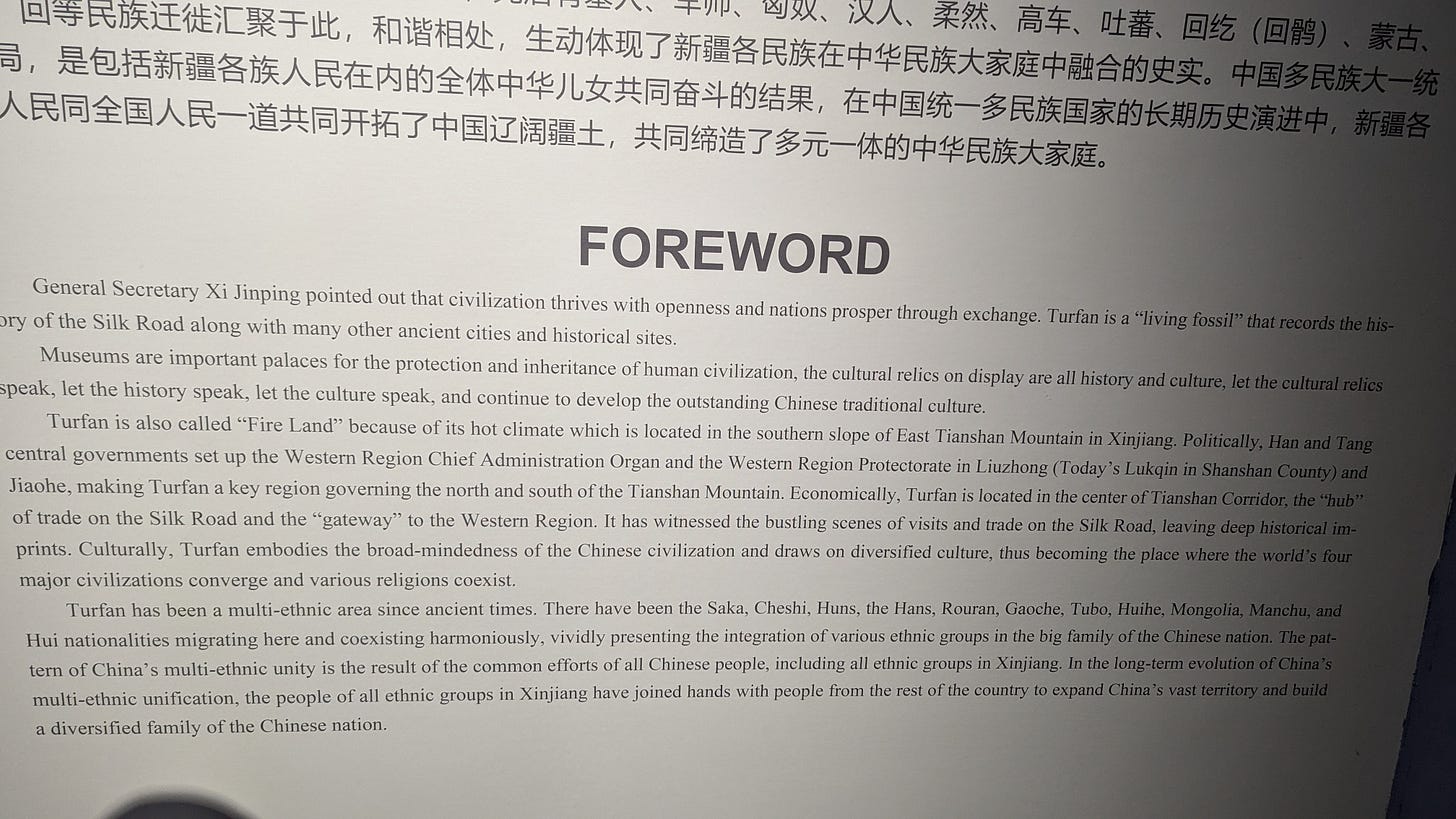

James A. Millward, Professor of Inter-societal History at Georgetown University, further examines the historiographical sleights of hand that frame modern China as a continuous, homogenous civilization-state, a narrative starkly at odds with the ethnically and culturally pluralistic reality of its history. “China, through another kind of historiographical sleight of hand, is considered to have always been something now called ‘China’: a unique, unitary cultural-political entity that, though ruled by an ‘emperor’ (huangdi 皇帝), was never ‘imperialist.’” In this revisionist view, the diverse ethnic groups currently within the PRC’s borders have always been intrinsically 'Chinese', even those whose integration into the state was historically recent. This narrative serves as a backdrop to contemporary policies, particularly in regions like Xinjiang, where the integration—or assimilation—of Uyghur populations into the broader Han-centric identity of China is both a policy goal and a point of international contention. The PRC’s ability to deflect international criticism over its treatment of the Uyghurs is bolstered significantly by its economic leverage, particularly through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative. Ironically, while promoting its global strategies under the guise of multicultural inclusiveness and cooperation, the CCP has intensified the securitization of Xinjiang, rallying BRI partners to support, or at least turn a blind eye to, its policies.

In Xinjiang itself, the sensation of being in a post-integration society is unsettlingly palpable. The high-security environment is less overt than one might expect, not because it is non-existent but because it is so thoroughly efficient. Friends recount similar experiences in Tibet, another region marked by an uneasy blend of cultural preservation and aggressive assimilation. Surveillance is not about the visibility of security measures but their invisibility; technology is so advanced and pervasive that you are often unaware of being watched, yet you are perpetually monitored. The occasional face scans in major cities starkly contrast with the seamless surveillance in the northwest, where, allegedly, the network is so proficient it knows where you are at all times.

IV. Power

When reflecting on China’s role in the global world order, I am reminded of a memorable moment during an introductory Global Affairs seminar at Yale—International Security, to be precise. In a room of about twenty students, our teaching assistant posed a question that seemed straightforward enough: how many of us believed we lived in a unipolar world dominated solely by the United States? I didn’t raise my hand and expected a minority of the typically-worldly (and arguably hawkish) cohort to raise their hand. Yet, to my surprise, approximately 90% of my peers confidently raised their hands in affirmation, leaving me in a stark minority. This moment was a stark realization of my own perspective, that perhaps the U.S.‘s unchallenged role in global power was more threatened than acknowledged. Was this majority stance a product of willful arrogance, misinformation, or a sort of denialism? It’s hard to say.

Even if the world has not reverted to bipolarity, it is undeniably multipolar. These recent travels to China have only reinforced this view; the notion of Chinese dominance in economic and political arenas isn’t just an imminent threat—it’s a present reality. However, this doesn’t seem to alter the pervasive fear of China in the West, particularly in the U.S., where there’s a palpable intent to deny the rise of this power at all costs. Without venturing into normative judgments, this denial of China’s role as a global power strikes me as empirically misguided and represents a myopic oversight by the Washington establishment.

The best analogy I can conjure relates to a misinterpreted and widely cited aphorism in the West: “May you live in interesting times.” This expression, often referred to as a traditional ‘Chinese curse’, ironically describes “interesting” times as periods of trouble and upheaval. Despite its common usage in English, reflecting a sense of irony over the troubled yet dynamic epochs, the saying is apocryphal. No actual Chinese source has been definitively linked to this exact phrase, which supposedly forms the mildest in a trilogy of curses—the next ones being “may you come to the attention of those in authority” and “may the gods give you everything you ask for.” Maybe, the misattribution of this “curse” and its acceptance in Western discourse serves as a metaphor for the broader misunderstandings that shadow our interpretations of China’s role on the global stage. In many ways, the West’s approach to China is akin to misinterpreting a nonexistent quote—creating a narrative steeped more in fear and fiction than in nuanced understanding.

V. Peking; Panopticon

This pervasive state paranoia subtly permeates even the tourist experience, reflected in the observations of Vikram Seth in his fantastic travel memoir, From Heaven Lake: Travels Through Sinkiang and Tibet. Seth poignantly notes the paradoxical status of a ‘foreign friend’ in China:

The status of a 'foreign friend' or 'foreign guest' in China is an interesting if unnatural one. Officialdom treats the foreigner as one would a valuable panda given to fits of mischief. On no account must any harm come to the animal. On the other hand, it must be closely watched at all times so that it does not see too much, do too much on its own, or influence the behaviour of the local inhabitants. 'We have friends all over the world,' announce banners slung up on the façades of hotels, but officialdom is disturbed by too much contact between Chinese and non-Chinese. They are horrified by affairs between Chinese and foreigners, especially if the woman is Chinese. From time to time this attitude bubbles over in tirades in the official press, but there is nothing like the xenophobia of the Cultural Revolution, when Beethoven was banned and diplomats beaten up by mobs.

My personal journey resonated with this guarded hospitality. With the exception of the commercial magnets of Shanghai and Shenzen, where foreigners are a dime a dozen, there exists a palpable, paternalistic oversight. Throughout my trip, every movement was facilitated through mega-apps—platforms designed to be omnipotent yet inaccessible to foreigners lacking a Chinese ID, thereby reinforcing a sense of exclusion. Without the graciousness of our hosts and the bonds formed with friends in the Mainland, navigating the intricacies of daily life would have posed a formidable challenge. The necessity of carrying my passport constantly, to gain entry to monuments, pass security checkpoints, and even access certain streets in Beijing, felt less like a precaution and more like a mandate.

Surveillance extends its reach into unexpectedly personal realms as well. The act of retrieving toilet paper from a public restroom required scanning a QR code linked to my face—a stark and somewhat surreal reminder of the state’s pervasive eye. This omnipresent surveillance is often normalized to an astonishing degree. One begins counting cameras out of curiosity, quickly losing count as the numbers climb into the dozens within minutes - not just in high-security regions. The realization dawns that this surveillance apparatus is not just a feature of the urban landscape but an ingrained part of life here.

Yet, many friends I encountered seemed to weave this reality into the fabric of daily existence, often discussing the trade-off between privacy and safety. They touted the eradication of crime and the emergence of a ‘high-trust society.’ However, this purported trust, facilitated by an omnipresent governmental gaze, raises the question: Is this trust truly organic, or is it a byproduct of a meticulously induced social order? Does it even matter, if these seemingly obvious benefits are clear to most? This question lingers, unanswered, as the benefits of such a society are praised—less crime, more safety, ostensibly a better life for most. Life, undeniably safer for most, comes with invisible shackles: tacit affirmations of a system where personal freedoms are often sacrificed at the altar of communal security.

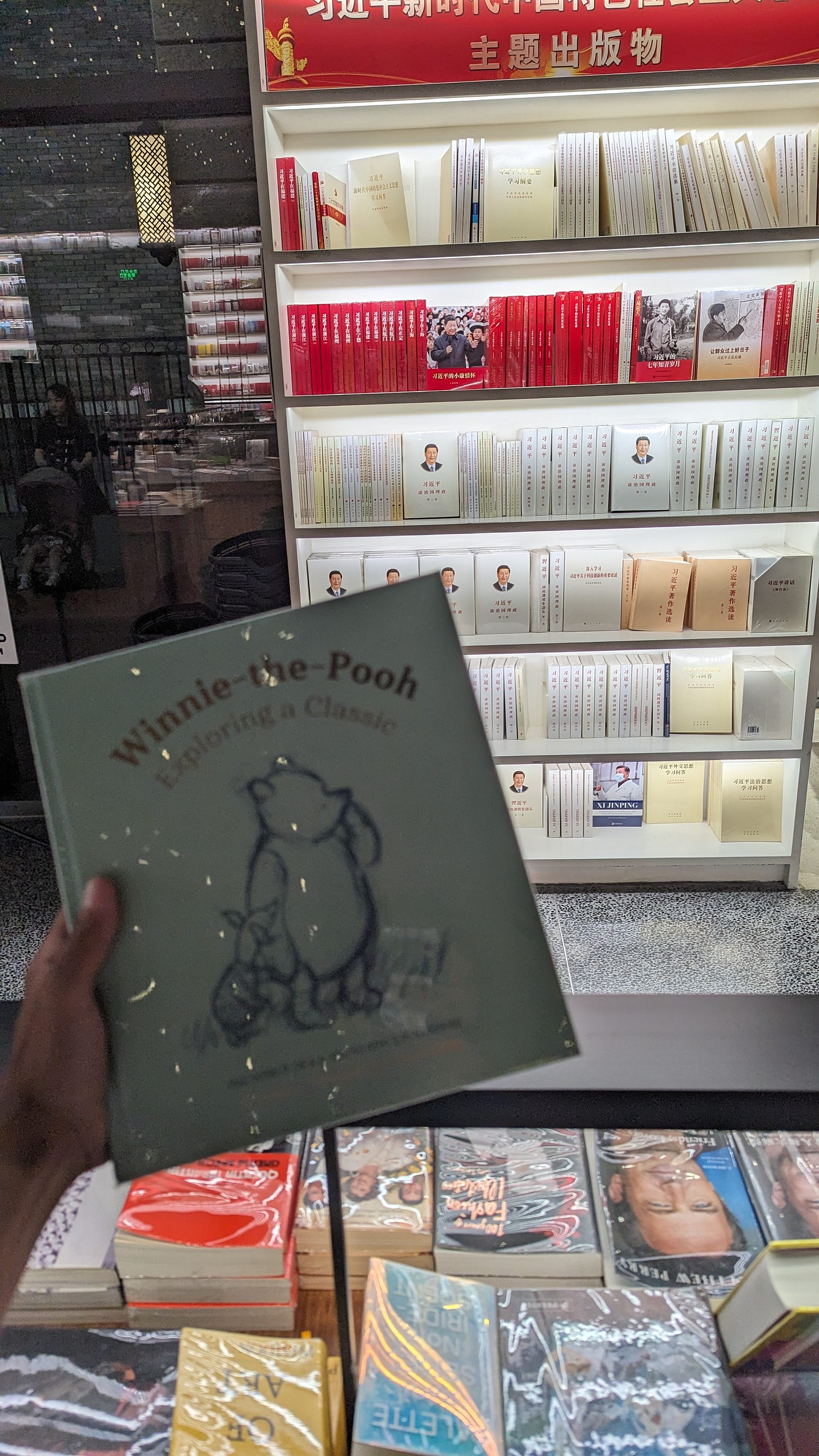

This surveillance extends its tendrils into the virtual realm as well, permeating everyday communications with an almost Orwellian oversight. On WeChat, a platform that serves as the digital town square, messages containing seemingly harmless memes vanish into the ether, never reaching their intended recipients. Observing this firsthand is nothing short of chilling. Children joke about these disappearances, yet beneath their laughter lies a deep-seated adaptation to a culture where censorship moulds not only the information they receive but also the very structure of their behavioral norms. This digital curtain, which subtly but surely filters one’s worldview, instils a conformity that is both profound and disquieting.

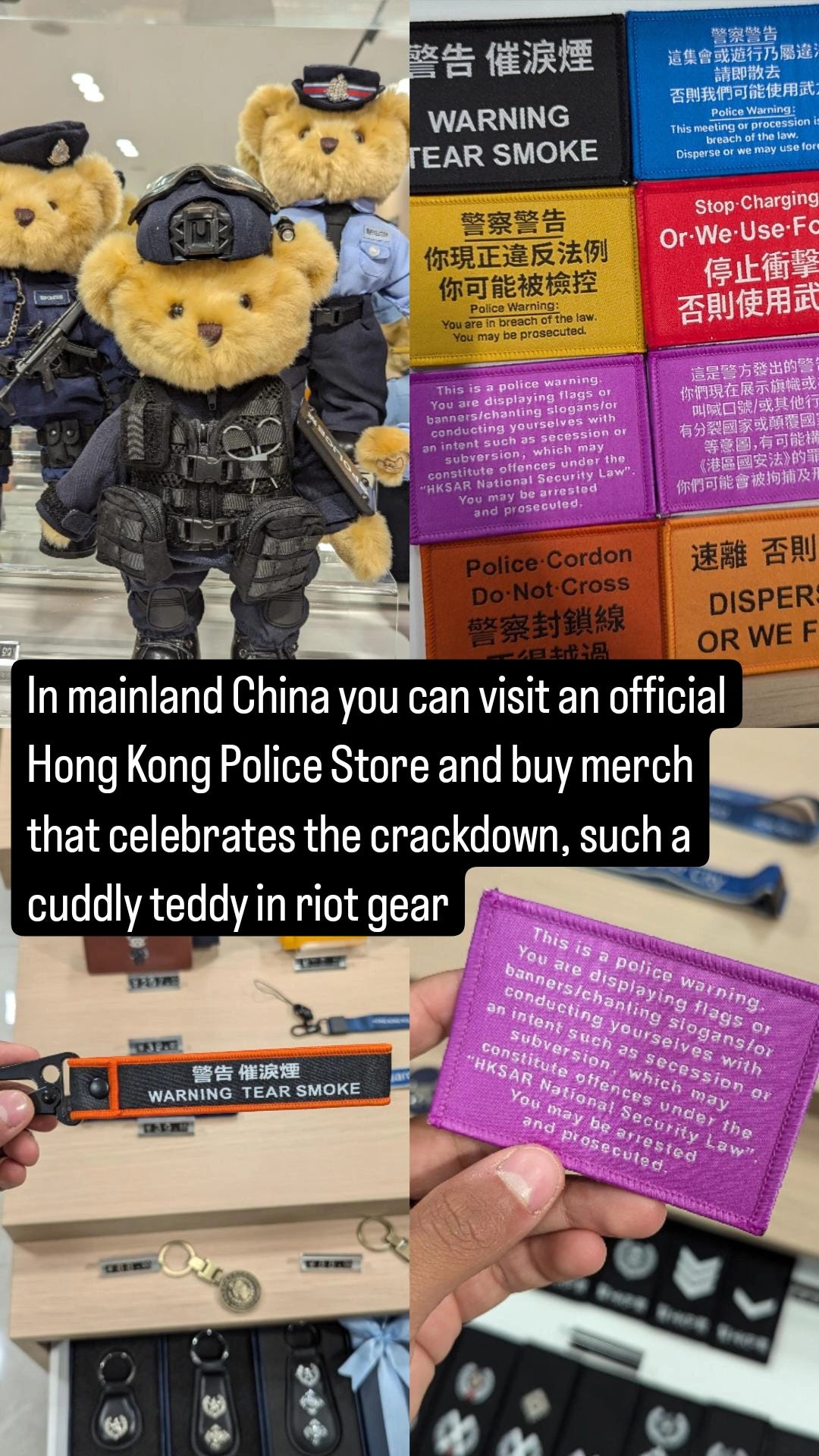

Amidst this landscape, there emerges a peculiar resignation to the status quo. Conversations are peppered with offhand comments about figures like the Panchen Lama, or tongue-in-cheek jokes about Han integration—expressions that reveal a complex layer of coping through humour. Perhaps most startling was my encounter in Chongqing, where I stumbled upon an official Hong Kong police merchandise shop. The casual commercialization of disdain for pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong struck a jarring note, almost comical in its brazenness, underscoring a broader acceptance of political narratives that once might have incited outrage.

A conversation I had echoed a common refrain: “If you have nothing to hide, why fear?” Yet, this sentiment slices through the social fabric in two sharply divergent directions. For the majority, this rationale may suffice; however, for minorities like the Uyghurs, who find their most basic freedoms stifled, the implications are far more grave. Their practices, deemed subversive by the state, are not just hidden but are actively suppressed. This reveals a darker aspect of the surveillance state: the freezing of dissent and a pervasive self-censorship that dissuades any form of opposition against the state apparatus.

The chilling parallel extends beyond China's borders to India, where similar patterns of surveillance and control are beginning to emerge. The emerging apprehension that a new India might exclude its minority citizens is not just a troubling indicator but a tangible manifestation of defeatism, a surrender to the belief that the secular ideals of India are perhaps unreachable. The long-term consequences of succumbing to this pervasive sense of helplessness are already becoming apparent. The danger of stumbling into the abyss of ‘learned helplessness’, where individuals feel so powerless that they disengage from social and political processes altogether, cannot be overstated.

A conversation with a Uyghur activist after the trip underscored the profound difficulties in building coalitions and garnering support against such a backdrop. The activist highlighted a troubling trend: over time, with sufficient suppression, public support dwindles, and the status quo becomes not only unchallenged but unchallengeable. This erosion of active civil engagement marks a significant victory for authoritarian practices, effectively quelling the collective voice that could otherwise advocate for change and reform.

VI. What would Said Say?

One of the biggest culture shocks was the predominance of domestic tourism in China, which presents an intriguing canvas of consumption, cultural exploration, and sometimes, conspicuous commodification. Tourist routes flourish, spiralling around modern statues perched atop mountains and traversing landscapes both breathtaking and utterly transformed by human presence. This phenomenon is less about the solitary contemplation of nature and more about the collective celebration of accessibility and shared experience—or as the digital age dictates, an opportunity for WeChatification, where every scenic moment is captured, filtered, and shared.

Beyond the social media frenzy, the reverence for history and culture manifests impressively in the museums sprinkled across provincial towns. Here, throngs of families meander through corridors echoing with the silent tales of artefacts, each piece meticulously curated to narrate the grandeur of China’s past. Even the smaller museums, their tickets often sold out weeks in advance, are a testament to a burgeoning demand among local Chinese tourists for spaces that celebrate and disseminate historical knowledge. This fervour for engaging with the past is not just a leisure activity; it's a vibrant educational pursuit, imbuing young minds with a sense of continuity and identity.

However, as we move deeper into the extremities of the Chinese landscape, particularly where the Han majority fades, the narrative takes a more complex, sometimes darker turn. Here lies a curious blend of fascination and alienation—an Occidentalist fantasy within the Orient itself, giving rise to what could be described as a proto-neo-oriental-occidentalism, a term Edward Said might have pondered with both pride and perplexity.

This nuanced interaction is best observed in the way domestic Chinese tourists engage with the 'othered' realms of their nation’s western territories i.e. the Uyghurs, the Kazakhs, etc. The peripheries and their cultures are both exotified and scrutinized, consumed as spectacles rather than experienced as integral threads of the national fabric. In these encounters, there is a palpable tension between the celebration of diversity and the subtle, sometimes unconscious, imposition of a cultural hierarchy. The museums and tourist spots in these regions do not merely display history; they stage a narrative steeped in the power dynamics of visibility and control.

Historian James Millward suggests that the practices seen are not isolated phenomena but part of a broader shift in policy and perception that aligns disturbingly with a global rise in majoritarian nationalism and Islamophobia. Millward notes, “It is likewise tempting to associate the gradual PRC shift from centralized pluralism to Han assimilationism with the 2010s global wave of majoritarian nationalisms, with which it certainly shares some features. Yet skin-colour racism and xenophobia (while certainly present in China) do not play the same role as they do in fuelling North American, European and Australian white supremacy movements. China does not attract the flows of immigrants or refugees that have triggered public backlash elsewhere. The one common, nearly global factor that links China’s majoritarian nativism to that in Europe, North America and India is Islamophobia. Besides the Uyghurs, the PRC state has in the 2010s increasingly targeted the religious practice of its other Muslim peoples, criticized mosques that are too big or too ‘Arabic,’ and let online Islamophobia fester.”

In Turpan and Ürümqi, the city's main mosques, grand in their historical and architectural significance, are curated not as active sites of worship but as museums for the secular tourist gaze. Signboards erase religious significance, and prayer regions are cordoned off from ticketed tourists. This echoes an observation by the BBC, an experience that mirrored my own, where the temporal rhythms of prayer seem obscured, lost amidst the needs of tourism. “We try to find out when the next prayer time is but no one seems to be able to tell us," reports the journalist, underscoring a disconcerting disconnect. An official’s indifferent response, "I'm just here to deal with tourists, I don't know anything about prayer times," only deepens the sense of dislocation.

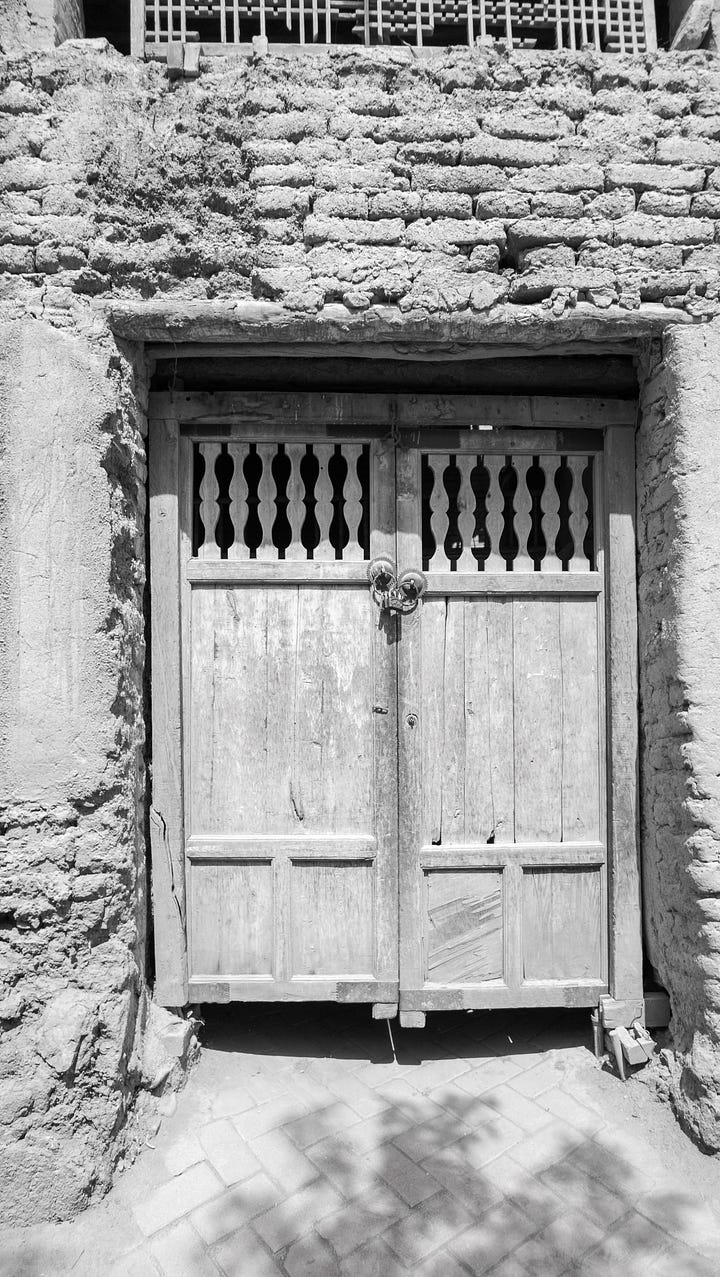

This shift is not isolated but part of a broader, more troubling trend observed in the smaller Uyghur villages near Turfan. Here, the stark realities of cultural displacement become palpable—houses remain padlocked, said to belong to Uyghurs who have been moved to reeducation camps, while those who remain capitalize on the passing Han tourists by selling trinkets and nuts, amid mosques that are no longer accessible for prayer but are closed off, symbols of a culture under lock and key.

Moreover, there is an undeniable orientalization of Uyghur culture, where its rich history and tradition are repackaged for consumption in a manner that borders on historical fetishization. Tourists don elaborate costumes reminiscent of scenes from Star Wars’ Tatooine or Mad Max, using the cultural backdrop as mere aesthetic scenery for fashion shoots. This reduction of a deep and tumultuous cultural identity to mere scenery is jarring—a historicization of the present, where the lived experiences of the Uyghur people are overshadowed by a narrative constructed for and by the tourist's eye. What would Said say, indeed, about this internalized orientalism? Would he see it as a mirror reflecting the broader orientalist attitudes that he critiqued, now reconfigured within the borders of the Orient itself? Perhaps he would view it as a complex dialogue—a continuous negotiation of identity and power, where the 'other' is both within and outside, simultaneously part of the self and apart from it.

These observations prompt a reflection on the nature of these ‘Potemkin villages’—idealized facades crafted to obscure a less palatable reality. Much like the villages staged to impress Catherine the Great, these spaces in China serve a dual function: they boost local economies and sustain a narrative convenient for the state and palatable for the tourist. Yet, beneath this veneer lies a complex, often painful story of a people whose everyday realities are veiled, and whose cultural essence is commodified. This raises profound questions about the ethics of tourism and cultural representation in regions marked by political tensions and cultural erasure. How do we navigate these spaces as outsiders, and what responsibility do we bear to look beyond the curated narratives presented to us? The answers are elusive, revealing the complex dance between seeing and understanding, between the tourist’s gaze and the lived reality of those who are, unwillingly, made a spectacle.

VII. A Toast

Closing this chapter—especially with an uplifting note—proves a daunting task. The gratitude I hold for my hosts in China is immense. These travels have been, without a doubt, some of the most enlightening and emotionally charged of my life, with a lot more to reflect on and write about. In moments like these, when the residue of experience clings more stubbornly than words allow, it is often to poetry we turn. Thus, as we bid farewell and go—’East and West’— let us close with the timeless verse of Du Fu, the great Tang poet. Here’s a ‘A Toast for Men Yun-Ch’ing’ translated by Florence Ayscough:

Illimitable happiness,

But grief for our white heads.

We love the long watches of the night, the red candle.

It would be difficult to have too much of meeting,

Let us not be in hurry to talk of separation.

But because the Heaven River will sink,

We had better empty the wine-cups.

To-morrow, at bright dawn, the world’s business will entangle us.

We brush away our tears,

We go—East and West.

so long,

BM

(All errors are my own, and a by-product of editing this on a slow boat from China)

Insightful.