Dearest readers,

Surprisingly, we are now ten chapters (or months) strong into this whimsical journey that is Ink-uilab. Nevertheless, I must confess: my penchant for procrastination has caught up with me this month and I find myself scrambling to pen this chapter in the final minutes of March (Although, Substack is certainly to blame as it randomly deleted my near-complete draft of this chapter). As Julius Caesar would have said, "Beware the Ides of March," and indeed, I should have heeded the warning, lest my own procrastination plot against me like Brutus.

But fear not, dear reader, for the show must go on! This one features South Asia’s favourite simpleton, a sacrament in Saudi Arabia, and societal separations.

This month, I had the fascinating opportunity to travel to Saudi Arabia. Initially, I intended to title this chapter of Ink-uilab "On Sand and Saud," but as I'm still digesting the experience, I'm striving to better articulate it in a way that not only does the country justice but also ensures that this visit to the KSA won't be my last. Here are some scattered thoughts:

I had the privilege of visiting the holy cities of Mecca and Medina for Umrah. The experience was nothing short of magnetic – a spiritual journey that leaves an indelible mark on the soul. Mecca, the holiest city in Islam, is a breathtaking testament to the ethnographic diversity and the vast reach of the Islamic faith. As you walk around the Kaaba, the sacred focal point of Muslim worship, you cannot help but be awestruck by the magnificent mosaic of cultures and traditions that converge in this spiritual epicentre. A haberdashery of headgear, from the intricately woven turbans to the traditional fez and Kazakh Kalpak, adorns the heads of countless pilgrims from around the globe. A myriad of beard styles - some salt-pepper, some red-stained - each reflecting the unique identity of the wearer and their cultural origins, adds to the diversity of human experience. The air is filled with a compendium of languages, a symphony of linguistic diversity, as pilgrims of various nationalities and ethnicities recite their prayers and converse with one another. I am still ruminating on the profundity of this pilgrimage and hope to share my reflections with you in a subsequent chapter.

Jeddah, in parts, is stunning! Al-Balad, in the historic heart of the city, harkens back to the city's origins in the 7th century. As you meander through the labyrinthine streets, you may be tempted to think that Al-Balad is a veritable maze – perfect for aimless wandering and escaping the relentless sun.

While I am in awe of Al-Balad's historical charm and architectural splendor, I cannot ignore the current efforts to 'sanitize' the district as part of the government's ‘Charm Offensive.’ As an influx of investments and development projects flood the area, one cannot help but worry that the authenticity of Al-Balad's cultural fabric might become diluted. Upper West Side-style cafes are tucked into little alleyways, and old buildings are being razed to be replaced with aesthetically pleasing, albeit soulless, replicas. Gentrification is a double-edged sword, and the government must tread carefully to ensure that the soul of this enchanting old town is preserved for generations to come.

I would be remiss not to discuss the depiction of culture in the country through the lens of the British television series, "Yes Minister." For those unfamiliar with the show, it is a stellar BBC parody of the inner workings of the British government, shedding light on the sometimes absurd and often frustrating bureaucracies of the British Civil Service. In one particularly memorable episode, the British minister, Jim Hacker, finds himself on an official visit to a Middle Eastern sheikdom to finalize a major contract for a UK firm. The Minister, having learned that the country is dry, arranges for liquor to be available on the sly. As you can imagine, this leads to a series of comical misunderstandings and mishaps, as the minister and his entourage grapple with the cultural norms and political complexities of the region:

While waiting for a taxi in Konjic, a picturesque town in central Bosnia, I closely observed a busload of Arab tourists. In an attempt to both satarize, and ethnographically record the moment, I penned a lampoon poem titled In a Cloud of Oudh. Given its satiric style and amateurish imitation of R. Dahl, I suspect that this piece may not find an audience anywhere but here:

I apologize now for this rhyme, its matter so crude

I hope it isn't misunderstood or misconstrued

But have you ever been so lucky as to have viewed

A bus of Arab Tourists: the whole familial brood?

At first they announce their arrival upon a cloud of OudhThen hydraulic doors open and out they're strewed

Take this family of five, for example, a typical similitude

And watch their generations chatter in polarized feud.

The bearded patriarch - either a Suleiman or Mahmoud,Who loves his gold black, his belly pat, his meats stewed

And his veiled wife, in plain black, strictly mustn't be wooed

His heir, yes that one, the sun-glasses and black shirt dude,

Lingers with his partner, not wife, in a state of lassitude.

Her headscarf glitters, and her back's tattooed

But hushhh her parents don't know, lest the disrepute.

Their gremlin child, if I may, is rather rude

Sets forth to distract us with a charming interlude

And runs around the bridge until he falls - chaos ensued

Cries echo in the valley and ruin the mood

His grandmother attempts a village-remedy but its no good

And then finally, lollipop in mouth, ipad in hand, eyes glued

Our wailing adolescent, the pram-ridden king, is finally subdued.Back to our familial tourists - their tale continued:

Father and Son, both heavily perfumed

Clash like antipodes, their ideologies skewed

His grandfather traded spices in Medina, bowed in sanctitudeNow his son parties in Mallorca, yachting in the nude

It began when they cried for justice and revolution brewed

Son danced the streets while his father boo-ed

The young welcomed change with drums and flute

The old stood strong, uninspired and resoluteBut since the monarch returned, now twice removed

They've declared democracy dead, liberty lewd

Their taxes are zilch - and as long as they salute

They're rewarded with luxury tours for servitude

Their hotels imbibed, gold-gilded, smoke-filled cherootsAnd their aircon buses laying down a new silk route

The balancing act wanders beyond the bus, and will now collude

To take family selfies, smile, act and delude

Long forgotten are their differences, on Damascus and BeirutAnd insinuations on imperialism, Islam and Likud

Observe now, fellow traveler, as politics become moot

When the motley caravan unites, searching of halal food.

South Asian Literature's Favourite Jester:

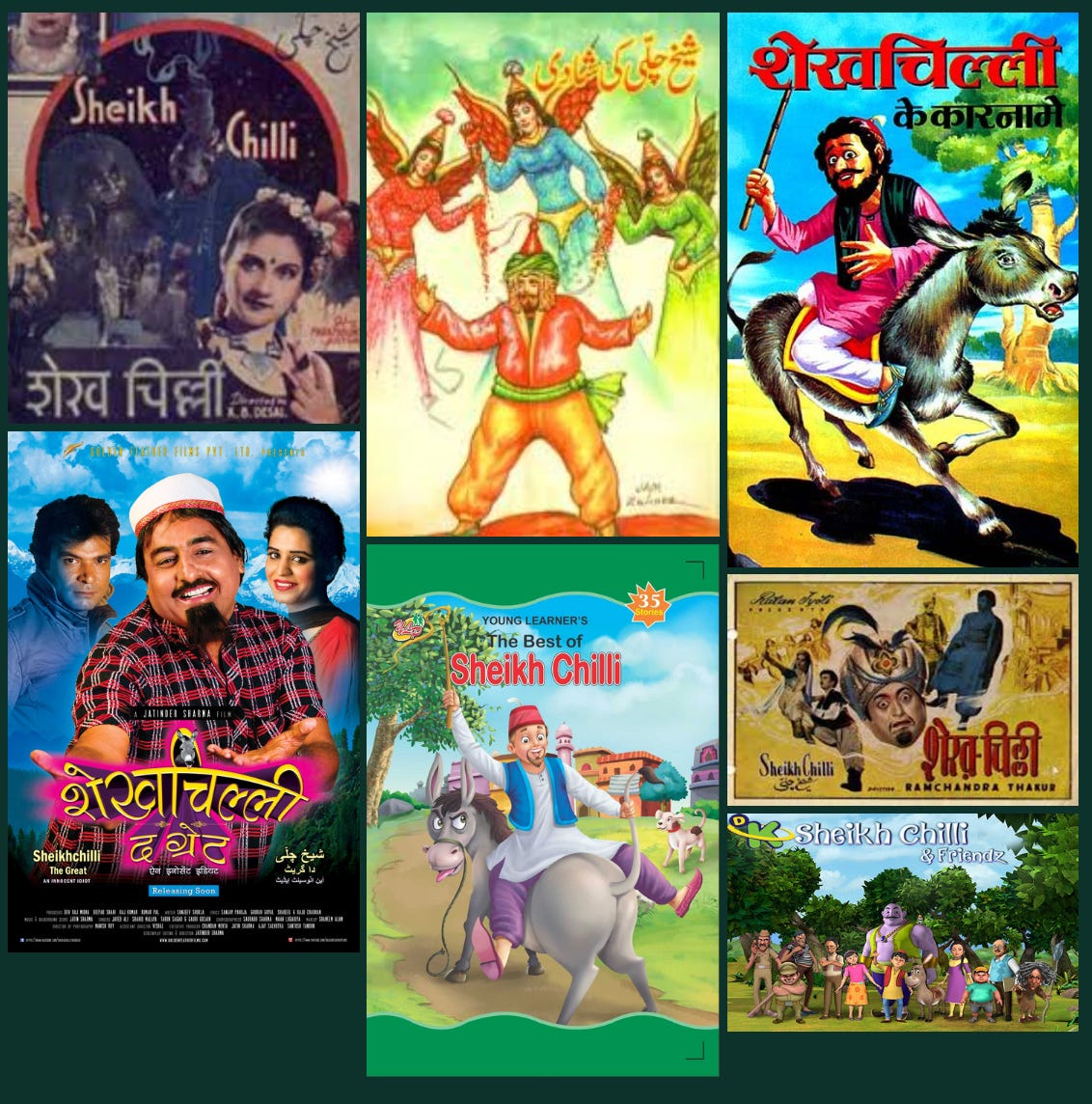

Meet Sheikh Chilli, the stock jester of South Asian folk tales. An absent-minded moron with a disregard for the laws of nature, his bumbling idiosyncrasies have been captured through oral storytelling, joke books, and the screen, and entertained children for decades. A typical example of the jester's tales might involve him daydreaming of himself as a king, or marrying a princess. It would end with the fantasy terminating, the dreamt-up castle vanishing into thin air and the lost Sheikh being jeered at by a crowd (and the amused reader).

The comedic follies of the simpleton Sheikh Chilli are pervasive in South Asian folktales. But how did a 17th-century Sufi scholar renowned for his wisdom come to eponymize the stock fool of subcontinental stories?

Inspiration for moronic character appears to originate from Sheikh Chilli (AKA Abdul-Karim Abd-ur-Razak), a 17th century Qadiriyya Sufi saint with a reputation for wisdom and generosity. Unfortunately, not much is known about the namesake Sufi scholar. The saint's name appears to be a distortion of ‘Chehli’, meaning forty in Persian, reminiscent of the forty-day ritual of chilla, or fasting and solitude. Chilli was a dervish (ascetic) of the Qadiriyya sect of Sufism and likely partook in the chilla rituals that earned him his name. The scholar is considered to be the mystical master of Prince Dara Shikoh, who was the son of Emperor Shah Jahan and heir-apparent to the Mughal throne. It is possible Chilli inspired the princely scholar's liberal beliefs in the harmony of Islamic Sufi and Hindu Vedanta philosophy. Shikoh would go on to pen a treatise on comparative religion, called Confluence of the Two Seas (Majma-ul-Bahrain) on the pluralism of Sufic and Vedantic thought. He would, however, be executed in 1659 on orders of his brother Aurangzeb, during the struggle for the Mughal throne.

Of course, it would be unfair to mention Dara Shikoh without paying homage to Professor Supriya Gandhi's book, her definitive biography on the Mughal prince. ‘The Emperor Who Never Was’ explores the life of Dara Shukoh, and demonstrates the folly of burdening historical figures with present-day conjectures.

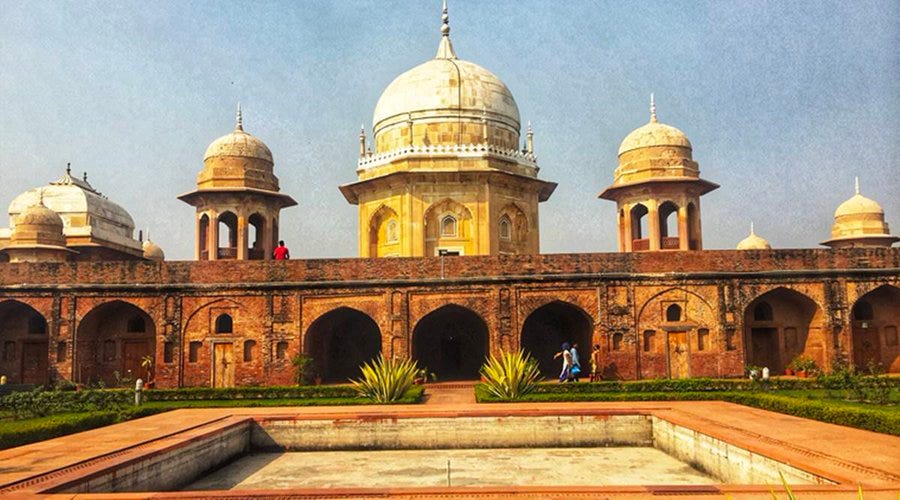

Sheikh Chehli, the ascetic, died in 1650. His sprawling mausoleum complex in Thanesar houses two tombs, a madrasa, a masjid, and a garden terrace - and is dubbed the 'Taj of Haryana.' The red-sandstone complex is adorned with intricate floral motifs and 'chaitya' moldings:

But, the question stands: How did this wise ascetic happen to lend his name to South Asian stories' ubiquitous fool? There is scant research on the journey of the eponym into the consciousness of the subcontinent's folk stories. To uncover the evolution of the character we must follow the Sheikh Chilli trope back in time:

One of the first references to Sheikh Chilli in literature is a book titled "Folk tales of Hindustan by Shaikh Chilli" published in 1886 by 'Himalayan Press' in Rawalpindi. While the book, sadly, appears to be lost to history - it does reveal a fair bit about the mystery at hand: This 1886 Sheikh Chilli book appears in the 1888 Catalogue of the Library of the India Office (British Raj). It is also cited as the source of an adapted and translated short story about Sheikh Chilli in the 1893 edition of the (now-defunct) French periodical Mélusine (Vol 6.).

The editors of the French periodical (Gaidoz & Rolland) credit a 'Miss Wadia' for the original English story, stating it was written by her under the pseudonym Sheikh Chilli and published in a collection in Rawalpindi in 1886. The editors also mention that Miss Wadia likely wrote the book based on "(trans.) stories learned by heart" - clearly implying that Sheikh Chilli's comedic antics found their way into print through an oral tradition of folktales in North India.

In 1893 again, three Sheikh Chilli folktales appear in the monthly periodical 'North Indian Notes and Queries (Vol 3).' Notably, the editor of this periodical was William Crooke, a prominent British orientalist and a key figure in the study and documentation of Indian folklore

Crooke's periodical was "devoted to the systematic collection of authentic notes and scraps of information regarding the country and the people." It was a prominent record of traditional folklore - and would go on to collate many Sheikh Chilli stories from the United Provinces. Unlike other such collections of the time, Crooke's periodical generally acknowledged the people who provided folklore, and also tried to gather information from a broad spectrum and geography of Indian society. It however vastly ignored the narrative contributions of women. It is suggested that the periodical's provision of an outlet for the Indian voices which lamented the loss of the past and a Hindustani 'civilization' was disliked by the governing elite of the time, and this led to the marginalization of Crooke within the British bureaucracy.

Our bumbling protagonist also makes an appearance in the Government Gazette of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh from 1896 in a rather quixotic context.

The report records the damage done to agriculture in Sultanpur district "by the ravages of an insect pest known locally as Sheikh Chilli"

Interestingly, Sheikh Chilli and Mullah Nasreddin share striking similarities, both being comical and sometimes wise characters in the folklore of their respective regions. Mullah Nasreddin, also known by various names such as Nasruddin Hodja and Khoja Nasriddin, is a beloved figure in the Muslim world from the Balkans to China. A hero of humorous short stories and satirical anecdotes, his tales often carry a subtle humor and a pedagogic nature. They also always feature his side-kick, a donkey. Like Sheikh Chilli, Nasreddin's existence remains a topic of debate among scholars. Although there is no definitive information about the date or place of his birth, some archaeological evidence points to a tombstone in Akşehir, Turkey, which could be related to him. It's fascinating to observe how these two distinct (stock) characters have captured the imagination of countless storytellers and audiences alike, becoming timeless symbols of humor and life lessons in South Asian and Middle Eastern folklore.

By the early 1900s, the comedic tropes of Sheikh Chilli begin to appear widely in literary periodicals, and standalone collections of stories are published - like 'The Life of Sheikh Chilli' by Muhammad S. Hussain, published in Lucknow in 1901. In 1900, the English writer Flora Annie Steel cast Sheikh Chilli as a character in her 'Voices in the Night.' Her writings are folk-inspired, having lived in India for 22 years.

I’ll leave you with Steel's vivid caricature of Sheikh Chilli, the ubiquitous jester of subcontinental stories:

"Sheikh Chilli, the pantaloon of India; the man of straw, the lover's dupe, the butt of every one; the type which, in varying form, plays its part in the serio-comic tragedy of sex all over the world ... ... Sheikh Chilli, whose beard any one can pull, whose wife is never his own, whom a child can deceive"

As always, some verses, in parting:

During a recent walk in London, I was reminded of R Parthasarathy's poem Exile. Parthasarathy's poetry reflects the dilemma faced by many Indian writers who grapple with using a language that is not their mother tongue or rooted in their cultural tradition. This dilemma led him to incorporate Indian, specifically Tamil, elements into his English poetry.

In 'Exile,' the first part of Rough Passage, Parthasarathy confronts the contrast between European and Indian cultures, as well as the impact of British culture on his own identity. Born in India but raised in England, the poet grapples with a sense of loss within his native culture and feels compelled to rediscover his roots. This exploration of cultural dislocation and the search for a true sense of self are key elements in Parthasarathy's poetry:

lamps burned in the fog.

In a basement flat, conversation

filled the night, while Ravi Shankar,

Cigarette stubs, empty bottles of stout

and crisps provided the necessary pauses.

He had spent his youth

whoring after English gods.

There is something to be said for exile:

you learn roots are deep.

That language is a tree,

loses colour under another sky.

The bark disappears with the snow

and branches become hoarse.

However, the most reassuring thing

about the past is that it happened.

Dressed in tweeds or grey flannel,

its suburban pockets

bursting with immigrants -

‘coloureds' is what they call us

over there - the city is no jewel. either.

But ugly and wet.

Lanes, full of smoke and litter,

with puddles of unwashed English children.

On New Year's Eve he heard an old man

at Trafalgar Square: It's no use

trying to change people. They'll be

what they are. An Empire's

last words are heard on the hot sands

of Africa. The da Gamas, Clives, Dupleixs

are back, Victoria sleeps on her island alone,

an old hag, shaking her invincible locks

cheers,

BM

(All errors are my own, and a by-product of editing this for a second time, as Substack made the first version disappear :( )

Wow 🤩. As usual a treasure trove of information BM ! The poetry about my Neighbour’s was just too good . Had a good laugh 😆.