Dearest egos and alter-egos,

For starters, the newsletter this month is in perfect alignment with the recurrent celestial bodies - indeed, we've returned to our scheduled orbit! In other words, the May chapter of Ink-uilab will not be appearing in June.

On to more pressing matters - the alliterative title. Obviously, I must acknowledge - our ostentatiously orated title overflows with an opulence of 'O's, an orchestration undeniably not intended to obscure the objective of this original odditorium [for a demonstration of semantic somersaults, see Sir Humphrey Appleby obfuscating]. This month, Ink-uilab explores intellectual history, philosophy, and literature through the narratives of three fascinating characters. The theme of intoxication unites the enigmatic experiences of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the olfactory opus of Patrick Süskind, and the opium-imbued verses of Samuel Taylor Coleridge that punctuate this chapter.

As always, thank you for reading and engaging with Ink-uilab. May you opt to become an official member, subscribing at no cost, and in return, obtain this monthly magazine, uninterrupted, dispatched directly to your digital doorstep:

On Oppenheimer:

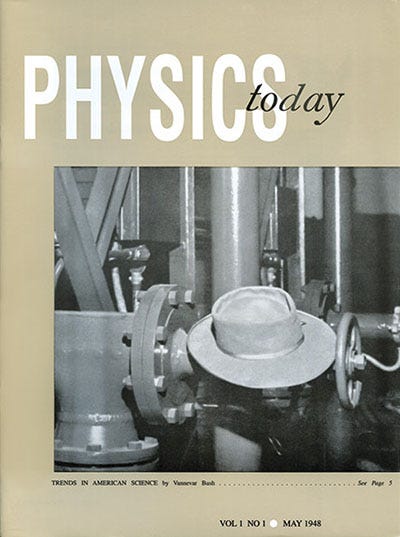

The opening act of this months’s Ink-uilab is the enigmatic J. Robert Oppenheimer, often referred to as the father of the atomic bomb. The ‘genius’ scientist, who wrestled with both the laws of physics and his own moral compass, is soon to be brought back to life in Christopher Nolan's highly anticipated biopic [here’s the trailer]. Born in 1904, J. Robert Oppenheimer was a man of remarkable intellect and diverse interests. He is best known for his role in the Manhattan Project during World War II, where his leadership led to the development of the atomic bomb. This role, fraught with moral and political dilemmas, positioned him at the core of a world-altering scientific breakthrough.

In a fortunate coincidence, a few months ago I read ‘Inside the Centre: The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer’ by Ray Monk, the acclaimed biographer. The book presents Oppenheimer as a compelling figure, painted with shades of power, conscience, and a complex personality. It weaves a narrative that sparkles with the pull of power and Oppenheimer's struggle to retain his moral grounding. The drama of his life was intense - from his connection with communists, who were unknowingly under surveillance (making Oppenheimer a target of the FBI), to his vehement opposition against the development of the hydrogen bomb amidst Cold War hysteria.

As an aside, Ray Monk has slowly become a personal favorite and his biography of Ludwig Wittgenstein deserves its own ode in a future Ink-uilab. Monk consistently manages to weave together incisive interpretation, detailed archival work, and narrative readability, crafting a book where you walk away with not just an understanding of the individual as a literary subject but also their personal philosophies and greater ambitions.

Outside his scientific pursuits, Oppenheimer led a colourful personal life. He penned poetry in his free hours, fostered a passion for New Mexico's landscape, enjoyed Marx, and was infamous for daredevil car rides meant to impress and intimidate his romantic companions. A remarkable excerpt from a letter (cited in Monk 2012) penned to a friend during an undergraduate Oppenheimer's tenure at Harvard furnishes us with an intimate window into his bustling existence. His narrative engenders an intoxicating cocktail of ceaseless activity, tinged with an undercurrent of ennui—a sensation not unfamiliar to many who have navigated the invigorating yet isolating halls of the Academy:

Generously, you ask what I do ... I labor, and write innumerable theses, notes, poems, stories, and junk; I go to the math lib and read and to the Phil lib and divide my time between Meinherr Russell and the contemplation of a most beautiful and lovely lady who is writing a thesis on Spinoza charmingly ironic at that, don't you think? I make stenches in three different labs, listen to Allard gossip about Racine, serve tea and talk learnedly to a few lost souls, go off for the weekend to distill the low grade energy into laughter and exhaustion, read Greek, commit faux pas, search my desk for letters and wish I were dead. Voila.

Oppenheimer's unique leadership abilities, in particular, evoke deep fascination. He was called to action during the wake of the Second World War and thrust into a position of authority. His genius was not so much in the originality of his insights, but rather in his remarkable ability to assimilate and critically apply new theoretical advancements, a talent that Paul Dirac lauded as his expertise 'as a chairman for a discussion or a colloquium.' As Ray Monk writes:

“True, Oppenheimer had never managed a laboratory (or anything) before, and as a physicist he was as purely theoretical as it is possible to be. And yet, in a way that amazed and impressed everybody who knew him, his entire life up to that point – his early interest in minerals, his determinedly wide-ranging education at Harvard, his absorption in the literature and art of America, France, England, Germany, Italy and Holland, his mastery of several European languages, his omnivorous devouring of all aspects of theoretical physics and his close following of major developments in experimental physics – turned out to be the perfect preparation for the task he had been set. He was the ideal man to lead Los Alamos, considered not just as a laboratory, but also as a new kind of city, one with far more than the normal proportion of extremely clever people and one, moreover, devoted to the accomplishing of a single, extraordinarily demanding task.”

Freeman Dyson, a fellow physicist, offered a compelling comparison in his book, ‘The Scientist As Rebel’ (2006), likening Oppenheimer to Lawrence of Arabia: “Lawrence was in many ways like Robert, a scholar who came to greatness through war, a charismatic leader, and a gifted writer, who failed to readjust happily to peacetime existence after the war, and was accused with some justice of occasional untruthfulness.” Dyson also commented on Oppenheimer's flaw—his restlessness, a restless inability to be idle. According to Dyson, this restlessness, paradoxically, might have hindered his creative work, as "intervals of idleness are probably essential to creative work on the highest level," just as Shakespeare, he noted, was habitually idle between his plays.

Oppenheimer’s role in the creation of the atomic bomb has been famously distilled into his haunting words after the first atomic explosion at the Trinity site:

We waited until the blast had passed, walked out of the shelter and then it was extremely solemn. We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita: Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, he takes on his multi-armed form and says, "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." I suppose we all thought that, one way or another

This iconic moment is rendered here, in an interview about the Trinity explosion, first broadcast as part of the television documentary The Decision to Drop the Bomb (1965):

A note on the translation of the famed Sanskrit quote: Monk’s translation of the phrase is certainly not common. According to Monk, “The Sanskrit word that Oppenheimer translates as ‘death’ is more usually rendered as ‘time’, so that, for example, in the Penguin Classics edition, the line is given as: ‘I am all-powerful Time, which destroys all things.’ In the famous translation by the nineteenth-century poet Edwin Arnold it appears as: ‘Thou seest Me as Time, who kills, Time who brings all to doom, The Slayer Time, Ancient of Days, come hither to consume’, which conveys an image diametrically opposed to that of a sudden release of deadly power. Oppenheimer, however, was following the example of his Sanskrit teacher, Arthur Ryder, whose translation reads: ‘Death am I, and my present task destruction.’”

When asked about his feelings regarding the atomic bombings in Japan during a visit in 1960, he offered a sobering reflection, "It's not that I don't feel bad about it. It's just that I don't feel worse today than what I felt yesterday." His words encapsulate a lifelong burden, the weight of a decision that forever changed the course of history.

Beyond unpacking Oppenheimer's academic pursuits or political quandaries, the biography explores some of his lesser-known histories and tendencies, veering into the realm of the bizarre. For instance, his attempt to poison his Cambridge tutor with a chemically-laced apple or his reported strangulation of the writer Francis Fergusson. These incidents sketch a man of powerful intellect, yes, but also one beset by inner demons.

Before you ask, here’s an excerpt from Monk about the poisoned apple incident: “In what looks like an attempt to murder his tutor, or at the very least to make him seriously ill, Oppenheimer left on Blackett’s desk an apple poisoned with toxic chemicals. The act seems charged with symbolism: Oppenheimer as the jealous queen leaving a poisoned apple for Snow White, the ‘fairest of them all’, whose beauty and goodness are admired by everybody. The incident was hushed up at the time, and none of his friends knew about it until they were told of it by Oppenheimer himself, usually in some more or less misleading version. That his feelings towards Blackett mixed fervent admiration with fierce jealousy, however, was obvious to those who knew him well.” (Monk 2012)

Monk’s book also highlights the compelling interplay between physicist personalities that characterized the era, introducing me to the fascinating character of Wolfgang Pauli. Known affectionately as 'the Wrath of God' among his friends due to his ruthlessly precise critiques of inexact thought, Pauli was quite the bold figure.

From an early age, Pauli was impervious to intimidation, unafraid to challenge even the esteemed Albert Einstein, once quipping, 'You know, what Mr Einstein said is not so stupid!' His rapier-like wit was also on display when a colleague, overwhelmed by Pauli's rapid-fire insights, pleaded for slower exposition. Pauli retorted, 'I do not mind if you think slowly, but I do object when you publish more quickly than you can think.' His cutting humour is encapsulated in his infamous remark about a convoluted paper: 'Das ist nicht nur nicht richtig, es ist nicht einmal falsch!' ('Not only is it not right, it’s not even wrong.'). I’d be excited to read a biography on the life of Pauli, but I can’t seem to find one -

Pauli's relationship with Oppenheimer, or 'Oppie' as his friends called him, was one of intellectual competition and playful camaraderie. He would affectionately imitate Oppenheimer’s habit of murmuring 'nim-nim-nim' when grappling for the right words. This led to Oppenheimer’s nickname as 'the nim-nim-nim man'. Pauli once quipped to Rabi, another physicist, and mutual friend, that Oppenheimer seemed to treat physics as an avocation and psychoanalysis as a vocation, a statement that captures the intriguing multifaceted nature of Oppenheimer’s interests.

There exists a captivating photograph from this period, preserved in the annals of scientific history, that shows a debonair Oppenheimer, cigarette in hand and hat on head, deep in conversation with Rabi and another American physicist, L.M. Mott-Smith. The three appear engrossed in thought, while Pauli, with a characteristic mischievous smile, stares directly into the camera:

On Patrick Süskind’s Das Parfum:

Patrick Süskind, a German author born in 1949, is well-known for his unflinching portrayals of the shadowed crevices of human nature. His magnum opus, ‘Perfume’, thrusts readers into the rich, olfactory universe of 18th-century France through the extraordinary journey of its protagonist, Jean-Baptiste Grenouille. I apologize, in advance, for the block quotes rendered in this section - I would be remiss if I didn’t include at least a few excerpts of Süskind’s first-rate prose.

A fleeting reference to this peculiar tale in a standout Indian art film - The Ship of Theseus (2012), an intriguingly well made collection of philosophical introspections. Directed by Anand Gandhi, a recipient of the National Award in 2014, the film probes existential inquiries of identity, justice, beauty, meaning, and mortality through three separate yet interwoven narratives. These three distinct fragments present musings from the experiences of a blind experimental photographer, an ailing Jain monk, and an enterprising stockbroker.

The second investigation in ‘The Ship of Theseus’, which has left an indelible mark on me, follows the journey of Maitreya, an erudite Jain monk brilliantly portrayed by Neeraj Kabi. Maitreya’s petition to ban animal testing in India faces a poignant irony when he is diagnosed with liver cirrhosis and finds himself reliant on the very practices he's been vehemently opposing. In my opinion, this narrative strand provides one of the most compelling on-screen philosophical explorations of religious absolutism versus pragmatism, and the personal dilemmas such a tension can evoke.

Viewers are invited to witness this raw depiction of human frailty, the entropy of the body, and the mapping of mortality, in its entirety. A captivating, humbling display of the impermanence of our existence, "The Ship of Theseus" is accessible for free and legal viewing here:

Returning to ‘Perfume’, its mention in the film indeed stirs an intriguing curiosity. The initial chapter of the film features an unorthodox photographer who, despite her visual impairment, uses her artistic instinct to capture evocative snapshots of her world. In a thought-provoking interview, she draws a parallel between her artistic intention and that of the protagonist of ‘Perfume’, each of them embarked on a quest “to capture the essence of everything.” But, how does one capture the essence of everything? And what compelling forces drive an individual to such an obsessive quest?

In the protagonist Grenouille, Süskind sketches an enigmatic figure - an unloved orphan endowed, or rather cursed, with an extraordinary sense of smell. This olfactory virtuoso navigates the aromatic labyrinth of the world around him with astonishing precision, even manipulating it to his whims despite his own lack of personal scent. Grenouille's life is a relentless pursuit of capturing and cataloguing, every conceivable aroma, a manifestation of the peculiarity obsession reflected poignantly in this excerpt from the novel:

He was not particular about it. He did not differentiate between what is commonly considered a good and a bad smell, not yet. He was greedy. The goal of the hunt was simply to possess everything the world could offer in the way of odors, and his only condition was that the odors be new ones. The smell of a sweating horse meant just as much to him as the tender green bouquet of a bursting rosebud, the acrid stench of a bug was no less worthy than the aroma rising from a larded veal roast in an aristocrat’s kitchen. He devoured everything, everything, sucking it up into him. But there were no aesthetic principles governing the olfactory kitchen of his imagination, where he was forever synthesizing and concocting new aromatic combinations. He fashioned grotesqueries, only to destroy them again immediately, like a child playing with blocks—inventive and destructive, with no apparent norms for his creativity.

This aromatic obsession of Grenouille's harkens back to the archetype of the collector, a figure I explore in-depth in Chapter Six of Ink-uilab.

In Süskind's masterpiece, we find ourselves entranced by the sensory symphony of his prose. The novel drenches us in an olfactory panorama so vividly painted, it can almost be smelt and tasted. The book opens with a potent distillation of the stenches plaguing 18th-century France:

The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of moldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlors stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets, damp featherbeds, and the pungently sweet aroma of chamber pots. The stench of sulfur rose from the chimneys, the stench of caustic lyes from the tanneries, and from the slaughterhouses came the stench of congealed blood. People stank of sweat and unwashed clothes; from their mouths came the stench of rotting teeth, from their bellies that of onions, and from their bodies, if they were no longer very young, came the stench of rancid cheese and sour milk and tumorous disease. The rivers stank, the marketplaces stank, the churches stank, it stank beneath the bridges and in the palaces. The peasant stank as did the priest, the apprentice as did his master’s wife, the whole of the aristocracy stank, even the king himself stank, stank like a rank lion, and the queen like an old goat, summer and winter. For in the eighteenth century there was nothing to hinder bacteria busy at decomposition, and so there was no human activity, either constructive or destructive, no manifestation of germinating or decaying life that was not accompanied by stench.

Yet beneath this malodorous miasma, Süskind's masterful narrative is also imbued with an almost Faustian tone and extensive use of intertextuality, creating a pastiche of the classics. This has been interpreted as an ironic allegory of the process by which the novel itself was constructed, a reflection of the perfumer's desire to mimic all existing scents paralleling Süskind's eclectic borrowing from pre-existing texts.

Adding to the intrigue surrounding "Das Parfum", Süskind himself lives as a recluse, eschewing photographs or interviews. His solitude calls to mind the sentiment he eloquently expresses in his novel:

We are familiar with people who seek out solitude: penitents, failures, saints, or prophets. They retreat to deserts, preferably, where they live on locusts and honey. Others, however, live in caves or cells on remote islands; some—more spectacularly—squat in cages mounted high atop poles swaying in the breeze. They do this to be nearer to God. Their solitude is a self-mortification by which they do penance. They act in the belief that they are living a life pleasing to God. Or they wait months, years, for their solitude to be broken by some divine message that they hope then speedily to broadcast among mankind.

Notably ‘Das Parfum’ has had a profound influence beyond literary circles, somehow reaching into the realm of metal music. The novel resonated deeply with Till Lindemann and Kurt Cobain, frontmen of the German alternative metal electro-industrial band Rammstein, and the American grunge band Nirvana, respectively. Inspired by the novel's odorous landscape, Rammstein released Du riechst so gut (trans. 'you smell so good') in 1995, while Nirvana offered a tribute in 1993 with Scentless Apprentice.

As always, some verses, in parting:

Delving into the intoxicating realms of literary inspiration, we turn our focus to Samuel Taylor Coleridge - a critic and philosopher, co-founder of the Romantic Movement in England, and, alongside his compatriot William Wordsworth, a Lake Poet. Today, we explore his alluring connection with opium, and its implications on his magical poem, ‘Kubla Khan.’

Opium, with its promise of euphoria and heightened imagination, has held an enchanting influence over various artists and creators, with Coleridge being no exception. The nexus of his creativity and opium is so entrenched that there is an entire Wikipedia article titled 'Coleridge and Opium.’ Yet, it is the eccentricity (and inebriation) of Coleridge that renders him utterly fascinating. For instance, his oeuvre includes “A poem is written on a piece of pale seaweed, while another seems to have been written in blood on a piece of Coleridge's skin that peeled off in the bath.” Straddling the liminal space between reality and dream, Coleridge constructs an imaginative landscape that enchants us with its enigmatic yet captivating beauty.

The story of Coleridge's composition of "Kubla Khan" is as fascinating as the poem itself. In the preface, he describes a profound opium-induced sleep wherein he dreamt of composing two to three hundred lines of poetry. It presents the drug as a peculiarly creative catalyst and is considered an early poetic encapsulation of a drug experience:

The author continued for about 3 hours in a profound sleep, at least of the external senses, during which time he has the most vivid confidence, that he could not have composed less than from two or three hundred lines … On waking he appeared to himself to have a distinct recollection of the whole and taking up his pen, ink, and paper, instantly and eagerly wrote the lines that are here preserved. At this moment he was unfortunately called out by a person on business from Porlock, and detained by him above an hour, and on his return to his room found, to his no small surprise and mortification, that though he still retained some vague and dim recollection of the general purport of the vision, yet, with the exception of some eight or ten scattered lines and images, all the rest had passed away like the images on the surfaces of a stream into which a stone has been cast, but alas! without the after restoration of the latter!

An intriguing pattern surfaces when we dive into the habits of individuals recognized for their extraordinary creativity, a pattern that intertwines genius with drug use. However, we must tread cautiously, as this observation is neither an endorsement nor a holistic analysis, but merely a pattern worth noting.

Take, for instance, the celebrated mathematician Paul Erdős, who relied on a daily dose of ten to twenty milligrams of Benzedrine or Ritalin. A concerned friend wagered that he couldn't abstain from amphetamines for a month. Upon successfully completing the bet, Erdős lamented, "You've showed me I'm not an addict. But I didn't get any work done. You've set mathematics back a month." Following the bet, he promptly returned to his amphetamine habit, supplemented with shots of strong espresso and caffeine tablets.

In a similar vein, we turn to philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, whose daily consumption appears as a veritable catalogue of vices. As depicted in Mason Curry’s "Daily Rituals" (2013), Sartre's daily menu comprised “two packs of cigarettes and several pipes stuffed with black tobacco, more than a quart of alcohol-wine, beer, vodka, whisky, and so on-two hundred milligrams of amphetamines, fifteen grams of aspirin, several grams of barbiturates, plus coffee, tea, rich meals”

Freud's relationship with cocaine, too, holds a compelling narrative. His letters vividly depict how he deployed cocaine as a crutch for his marriage and how the initial euphoria about this 'miracle drug' insidiously evolved into a haunting dependency, the specter of which permeates his interpretation of dreams and psychoanalytical writings.

Literary luminaries like Charles Dickens and Ernest Hemingway, composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and the macabre storyteller Edgar Allan Poe seemed to be navigating through an alcohol-induced haze. Yet, one wonders if these instances are mere selection bias or random cases, notwithstanding the pattern that seems to emerge. [See S. Wolfram’s ‘Idea Makers’ (2016), Mason Curry’s ‘Daily Rituals’ (2013), Colin Wilson’s ‘The Misfits’ (1989), and Mike Jay’s Psychonauts (2023) for a range of examples and counter-examples.]

Here’s a recitation of Kubla Khan that particularly resonates with me - delivered by none other than Benedict Cumberbatch (who also portrayed a drug-addled Sherlock Holmes and Patrick Melrose in the respective eponymous series):

I present to you an excerpt of Kubla Khan by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, an intoxicating poem birthed from the throes of an opium-induced dream:

Or, a vision in a dream. A Fragment.

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round;

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

….

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean;

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Godspeed,

BM

(All errors are my own and a by-product of editing this without the aid of any of the vices mentioned in the section above)

Arey Bhai aakhir Kehna kya chahte ho … too deep for a lay man like me 🥲